The real cost of food

The real cost of food

Can the market alone guide our food systems

towards more sustainability?

The market economy context

We live in what is referred to as a market economy, defined as “an economic system in which goods and services are made, sold and shared, and prices set by the balance of supply and demand1”, goods and services being defined as “the products and services that are bought and sold in an economy2”. In such an economy, people earn their living by selling goods and services in order to be able to purchase what they need, and it is believed that the price of goods and services exchanged is what determines to a large extent what people produce, sell and purchase.

The food sector is no exception and, like in other sectors, it is the market price of food products that has increasingly been the main factor explaining what is being produced and consumed. In this context, the cost of food is considered to be the total combined cost of all elements entering the production process. These elements comprise items such as labour, seeds, fertiliser, pesticides, fuel, and all other goods and services that are being bought or used3 that are required for producing a particular food product, including financial costs such as interests, reimbursement of capital for machinery and insurance.

For decades, it has been believed that the pricing system determined by the market was providing the best signals and incentives for both producers and consumers optimising their activities and allocating resources in the most efficient way so as to generate a maximum wealth and make the economy grow.

The market is at best shortsighted

One of the assumptions continuously referred to by the theoreticians of the market when they flaunt the merits of a market economy, is that the market must be perfect, perfection being achieved when “the sellers of a product or service are free to compete fairly, and sellers and buyers have complete information4”.

In fact, there has probably never been anywhere anything close to an ideal market! Competition is not free and fair when the market is dominated by huge companies who often create alliances for sharing the market and agreeing on prices or, on the contrary, when some of them decide to dump their goods in order to eliminate rivals. Neither is it fair when there are considerable imbalances among firms operating on the market regarding information and when there is a great deal of important information that sellers and buyers active on a market do not have. In fact, they usually only have very limited knowledge of what they purchase. It generally boils down to the price, the appearance of the good, some indications provided by the producer and past experience with the person with whom the exchange is taking place.

In other words, the market is a shortsighted deity to whom we have entrusted the management of our economy on the basis of a small part of the information required to understand what is actually going on. It is a deity who is everything but omniscient!

In particular, there is a whole set of crucial items on which the market and its operators have no information. These are items that matter but are not exchanged on the market. In the case of food and agriculture, they comprise essential elements such as

-

•Health and health threats (poisoning, malnutrition, resistance of germs to antibiotics, emergence and dissemination of pathogens, etc.);

-

•Soil, air, water and agricultural biodiversity (which has a central role in the production and composition of our food - e.g. microorganisms and earthworms, pollinators, fish and other seafood, crop and animal species, varieties and breeds);

-

•Climate (temperature, rainfall, wind, etc.);

-

•Soil and water quality (e.g. acidity, carbon and mineral content, salinity, toxicity);

-

•Poverty and human suffering, and others,

the state of which, depending on how it evolves, may generate major costs. This is illustrated by Figure 1 below.

However, these non-market costs are very real, and some of them directly translate in monetary terms such health care spending, destruction of housing and infrastructure because of extreme meteorological events to mention just two examples, while others such as psychological trauma and suffering or loss of cultural or artistic assets are more difficult to be properly compensated or replaced. As these costs are neither visible nor felt immediately by those involved in the market process, they are called externalities5.

Figure 1: Market and non-market costs and benefits of food production

Download Figure 1: Figure_1_RCF.png

The logical implication is that the information on the basis of which the market operates is incomplete and imperfect. Therefore, it is likely that the result obtained from a market process that responds to biased incentives and signals - i.e. the allocation of resources to various activities and the technology used - will not be optimal, as it rests on decisions by people who have access to information that fails to take into account a large part of reality. The chances for the decision resulting from this process of being optimal is probably comparable to the chances a shortsighted person who never shot a pistol has to reach the centre of a target positioned 200 yards away!

Some consequences of market shortsightedness

They are well known to those who are used to read hungerexplained.org [read] and many impact directly on the above-listed items that matter but are not exchanged on the market. These consequences are the result of biased decisions made when relying only on the signals and incentives provided by the market.

Choices are skewed because they are made on the basis of a subset of costs and benefits, those that are reflected in market prices, and decision makers consider de facto all other benefits and costs (including the major part of natural resources) that are not valued by the market as worthless.

immediate financial profit = (revenue from sales) - (costs of purchased inputs)

The implication is that the decisions will automatically opt for solutions that reduce as much as possible costs priced by the market; this will most likely cause an escalation of those real costs that are invisible to the market because they are considered as worthless. In other words, by relying on the sole market prices, decisions will give priority to those products and technologies that will be yielding the largest immediate financial profit, disregarding all other aspects.

This can be illustrated by an example. Suppose that, overnight, the government decided that all petroleum-based products were free. People would start overusing these products, for example by driving around just for fun and the industry would build cars with big thirsty engines. The consumption of these products would flare up in an extraordinary fashion. Similarly, we have been developing a food system that “consumes” gluttonously our natural resources (land, water, air and biodiversity) and damages our health because they are not goods that can easily be exchanged and valued on the market.

This is exactly what is happening nowadays in the food sector where, even though the organic market has grown [read], organic farmers have to compete unfairly with intensive, large-scale chemical farming that benefits from a system that provides it with misdirected agricultural subsidies and that is not charged for the damage it causes to the environment and to public health. Organic producers are penalised on the market despite the fact that they generate more economic value than conventional agrochemical agricultural producers [read].

Some recent estimates give an idea of the scale of the externalities generated by our food supply chains:

-

•Health:

-

•In 2019, there were 680 million chronically undernourished people in the world and more than 2 billion people experienced moderate food insecurity [read];

-

•In 2018, nearly two in five adults (38.9%) were overweight, representing 2 billion adults worldwide [read];

-

•Every year the use of pesticides causes approximately 200,000 deaths by acute poisoning [read];

-

•Biodiversity:

-

•According to FAO, about 75% of agrobiodiversity was lost during the 20th century;

-

•The number of farmland birds and insect biomass have also fallen drastically [read];

-

•Our food supply chains are responsible for 32% of terrestrial acidification and 78% of eutrophication6 [read];

-

•Our food also plays a central role in the degradation of our land resources [read]; and,

-

•Our food is the cause of 21-37% of total global greenhouse gas emissions resulting from human activities [read].

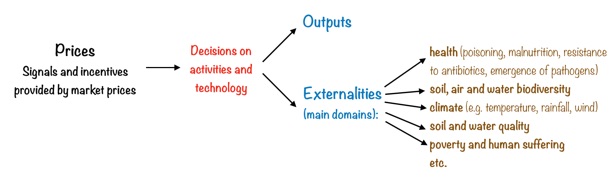

Figure 2, below, illustrates how market prices influence technological choices and create externalities.

Figure 2: The market prices, decisions, output and externalities process

Download Figure 2: Figure_2_RCF.png

More market flaws

In addition to being blind to major costs, the market is also time blind:

-

•It encourages producers to live in the present and to prioritise activities and technologies that are more productive now and not to care about their impact on future productivity;

-

•It urges consumers to give priority to their immediate well-being and to neglect future effects and costs that may arise from what they have consumed (on their health, on the climate, on the loss of biodiversity, on the degradation of landscapes, etc.).

The market is also space blind: decisions are only concerned with what happens directly to the individuals who decide, to their plot or their farm, but not with the impact their choices have on what is happening elsewhere (pollution of groundwater, streams and of the sea7, climate change, loss of pollinators, etc.).

Box 1: Some methodological considerations

The space and time blindness of markets is very representative of the ideological context in which we live. It is characterised by “presentism” (what matters is now, who cares about the future?) and egoism (what matters is my own pleasure, who cares about others?) [read]

This dominant ideology, whose roots date back two and a half centuries to the time of classical economists Adam Smith and David Ricardo [read], enjoyed a revival during the 1990s. This resurgence had serious implications on methods of analysis used in economics.

In the 1980s, for a short while, there were two competing schools of thought for economic analysis of investment projects for development. One was promoted by the World Bank and the OECD that was based on the use of computed border prices [read], and the other by the French Ministry of Cooperation that was analysing how the effects of an investment project were being transmitted and impacted on different agents within the economy [read in French].

Over the years, the computed border shadow price method became generalised, while the effects methods disappeared. This symbolises rather well the ideological domination of a vision of the economy where prices and liberalised international trade is what matters, while a more structural vision of the economy has all but disappeared, where the focus is, for a given action, on the ripple effect it generates and that is being transmitted throughout the structure of the economy.

This illustrates well how the market-based vision of the world has become dominant among economists and policy makers.

Pricing non-market costs and benefits

Rationale

The growing awareness of the deleterious consequences of abandoning food production to the vagaries and imperfections of the market has triggered attempts to try and improve the quality of information used by markets so as to reduce their blindness to costs and benefits that are not currently reflected in prices.

There have been huge efforts made by researchers over the years to try and estimate a price for non-market costs and benefits. The principle underpinning this work has been to give a money value - a shadow price - to these costs and benefits so that they could be “understood” by the market. This project is comparable to attempting to represent the four-dimensional space we experience in our everyday life on a simple line! Imagine the simplification this reduction requires and you will measure that the loss of information involved will be absolutely tremendous! This brings us back to the single indicator issue that we have already dealt with elsewhere [read].

The proponents of this approach nevertheless “believe in the power and potential of true cost accounting (TCA) and its role in accelerating the transformation of our food systems… [and they] champion its efficacy to better inform policy and practice and lead markets towards the healthy, sustainable, and equitable food systems we urgently need” in the words of Ruth Richardson, Executive Director, Global Alliance for the Future of Food, a foundation created in 2017 who is actively engaged in the forthcoming UN Food Systems Summit.

They also wish to propound a standardised valuation method in order to eliminate uncertainties on results and impose a reductive framework, simplified as much as possible so as to minimise the complexity of reality [read for example the summary of the recent publication Valuing the impact of food: Towards practical and comparable monetary valuation of food system impacts], so as to be able to compute one value, a shadow price, behind which the multidimensional complexity and tradeoffs typical of the food sector will be hidden.

Difficulties and shortcomings

It is challenging to standardise the computation of such a shadow price and even more awkward to come to an agreement on the method to be used. In some cases, it is based on the costing of foregone production (e.g. if the soil gets salty because it was not irrigated properly, it is possible to estimate the loss of output incurred; if people are sick or die from diabetes, the resulting decrease of production can be estimated; if pollinators disappear, the resulting loss of production can be quantified). In other cases, it is the cost of prevention (e.g. the cost for building anti-erosion infrastructure), or the willingness to pay (e.g. how much are people ready to pay for a particular landscape or forest to be protected?), or the cost of replacement, etc. that are used to compute the shadow price.

The evident problem is that depending on the approach taken (loss, prevention, replacement or willingness to pay for protection, to mention just these), the resulting shadow price of a particular item can be very different. Moreover, for a given technology, it may be needed to combine these approaches: this will be like adding apples, pears, crocodiles and worms into one bad and deciding that they be equivalent to a pile of grapes... or dollars.

And there are yet many more problems to be solved: how to add up a cost today with a cost tomorrow and yet another in twenty years (the systematic discounting of future costs that is usually recommended is one of the causes of our unsustainable practices) [read]? How to deal best with irreversibility of and impact? What should be the boundary within which to limit the analysis (the plot, the village, the country or the world)? How to add up the willingness to pay of the poor and that of the rich, of the rural and of the urban? Does one dollar paid or lost, have the same social value in the case it is paid or lost by a rich person or by a poor one?

From an ethical perspective, the blind and uncritical use of these shadow prices also carries the risk of offering to the public a scientised version of the “all-market ideology” where the market is presented as the universal solution that can fix everything in an optimal way, in other words, a new version of the market deity, adorned with complex computations.

These are some of the aspects that are crushed into one single dimension when specialists finally associate one unique estimated shadow price to a particular good. Given the multiplicity of choices made to come to this result, does it make sense to select the best of two alternative technologies on the basis of the sole cost estimate associated to them? Are these costs really comparable without taking into consideration all the decisions made while estimating them (some being rather arbitrary or based on values that are not universally shared)? Or would it be safer to leave them aside altogether?

T. S. Eliot was right: “The journey, not the destination matters…”. In this case too, it is not the resulting value that is important as much as the process that led to it and the required understanding of what is actually happening. The worst option would be to stick to a standard shadow price for a particular input, without making the effort of grasping how its use creates externalities! It would amount to just opening slightly the blinkers that the market-based ideology has managed to impose on us and it would leave us quite far from taking into account the impact of our food system in all its dimensions and complexity.

Why is the pricing of non-market costs and benefits valued by the private sector?

The shadow pricing approach is now strongly promoted and supported by some large multinational companies like Yara (fertiliser), Syngenta (seeds and pesticides) and Nestlé (food processing) who funded the above-mentioned study [read]. They are convinced that the approach is useful to them. They believe that “Businesses that recognise hidden costs and create opportunities in the transition to a more sustainable world will generate a strategic advantage in comparison to peers, be able to access capital at a rate that reflects their lower risk profile, and be well positioned to drive long-term value creation for society and shareholders” in the words of Diane Holdorf, Managing Director, Food and Nature, World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

It is clear from this statement that the overall declared objective of using food system impact evaluation to help “align the market dynamics of food and agricultural towards the social and human well-being targets of food system transformation” is just a sham. In reality, the objective of supporting efforts to value non-market costs in monetary terms is to create a triple opportunity for the private sector to:

-

•Gain a more positive image in the eyes of consumers who are increasingly concerned by the sustainability of our food systems;

-

•Simplify the multidimensional complexity of the sustainability issue to boil it down to just one dimension, money;

-

•Improve their position on markets (including financial markets) in order to further attract capital and boost profits and dividends paid to shareholders.

Potential usefulness of estimated prices

Despite all these shortcomings, these computed prices could be useful if handled carefully. For example,

-

•They could help estimate the tax that should be imposed on certain goods to reflect the externalities resulting from their use, in the case of inputs, or from their production, in the case of consumption goods. For the latter, it would vary according to the technology adopted. This would contribute to reducing the advantage given currently by market prices to goods with high negative externalities and encourage the transition to a more sustainable food production. However, taxing is only one aspect of the question. The second aspect is to find appropriate mechanisms for using the receipt of the tax to compensate those who suffer from negative externalities, to encourage practices with positive externalities and to support poor consumers as taxed goods will become more expensive. These mechanisms will have to be transparent so as to increase understanding and acceptability by the public.

-

•They could serve to establish a colour-based scoring system of the real cost of food on the pattern of existing nutritional scores (see for example the case of France’s Nutri-Score in French). This type of scoring would inform consumers and, hopefully, orient their purchases. For example, it would illustrate that “impacts of the lowest-impact animal products typically exceed those of vegetable substitutes, providing new evidence for the importance of dietary change”. [read]

-

•They could also be used as advocacy data and give an order of magnitude of some of the impacts of our food system. For example: Obesity is estimated to have a global economic impact of around $2 trillion annually, or 2.8% of global GDP [read].

However, because of the shortcomings of these shadow prices, they are likely not to be sufficient to guide the transition towards a sustainable food system. Supplementary measures, including specific regulations on the use of certain inputs or technologies such as banning use of toxic agrochemicals like neonicotinoids or dangerous food additives, prohibition of cultivation on steep slopes unless adequate erosion control measures are applied, fixing norms on the maximum level of presence of certain additives in food (like salt, sugar and others) and imposing official quality labels, as already mentioned earlier, will also be required.

These crucial supplementary measures will evidently have to be decided on the basis of detailed and comprehensive information on externalities generated by the food system and cannot be deducted from an aggregated item such as a shadow price. This points to the need for further and continuous detailed research on externalities created by the food system.

Conclusion

There is now ample evidence that our food system is not sustainable and that it generates huge negative externalities in the social, economic and environmental domains. The real cost of our food is far greater than what is reflected in the market prices that currently play the central role in the choices made by both producers and consumers.

Efforts have been made to try and assess the real cost of food. The fact is that the real cost of food cannot simply be evaluated on the basis of a computed cost expressed in monetary terms, as such estimates suffer from huge shortcomings. While calculated shadow prices may provide some aggregated information and can be of use, in particular, to estimate taxes and subsidies for guiding the actors of our food systems towards greater sustainability, they cannot be considered as a panacea, given the many limitations inherent to the way they are computed.

A detailed understanding of the processes that make our food system unsustainable is indispensable to whoever wants to design solutions for improving it. The unique indicator some propose - the shadow price - is insufficient and opaque, as its establishment requires choices that are made in a technocratic context. Relying exclusively on it would amount to give all the power of deciding to the market. Rather, what is needed is a set of indicators to account for all the dimensions of reality where costs are incurred and a good grasp of the mechanisms through which they are generated.

It is by examining these dimensions and comparing different production technologies that it is possible to decide which one of them is preferable in a particular context. This multidimensional analysis is essential in reviewing tradeoffs, negotiating and finally choosing responsibly actions to be taken in a democratic and transparent way.

This process is, of course, much more cumbersome and potentially lengthier than applying one price. But it is worth the effort, because an estimated shadow price hides the complexity of reality and the risk is high that its uncritical use would result in flawed decisions whose consequences might include some very unpleasant surprises that would not go in the direction of an improved sustainability of our food system.

Materne Maetz

October 2020

—————————————

Footnotes:

-

1.https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/market-economy.

-

2.https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/goods-and-services.

-

3.For those inputs that are not bought but produced on the farm (e.g. grain, hay and straw for animals), they are valued at market price.

-

4.https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/perfect-market.

-

5.An externality corresponds to a situation where the act of producing or consuming by an economic agent has a positive or negative impact on one or several other agents not directly part of the act, and where these affected agents do not have to pay for all the benefits that have accrued to them or are not fully compensated for the harm they have suffered. In practical terms, this often means that the costs of such externalities end up being met by future generations.

-

6.Eutrophication: the addition of nutrients to water in lakes and rivers, which encourages plant growth that can take oxygen from the water and kill fish and other animals (Cambridge Dictionary).

-

7.A typical example of such impact is the development of green algae on Brittany’s coast that is usually explained by the presence of a very intensive agriculture in the hinterland (piggeries in particular).

—————————————

To know more:

-

•S. Lord, Valuing the impact of food: Towards practical and comparable monetary valuation of food system impacts, Global Alliance for the Future of Food, Food System Transformation Group and World Business Council For Sustainable Development, 2020.

-

•The true cost of food, editorial, Nature Food 1, 185, 2020.

-

•The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), TEEB for Agriculture & Food: Scientific and Economic Foundations, UN Environment, 2018.

-

•J. Poore and T. Nemecek, Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers, Science, 2018.

-

•The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) website.

Selection of past articles on hungerexplained.org related to the topic:

Last update: October 2020

For your comments and reactions: hungerexpl@gmail.com